Global warming could harm the oceans' most important organism

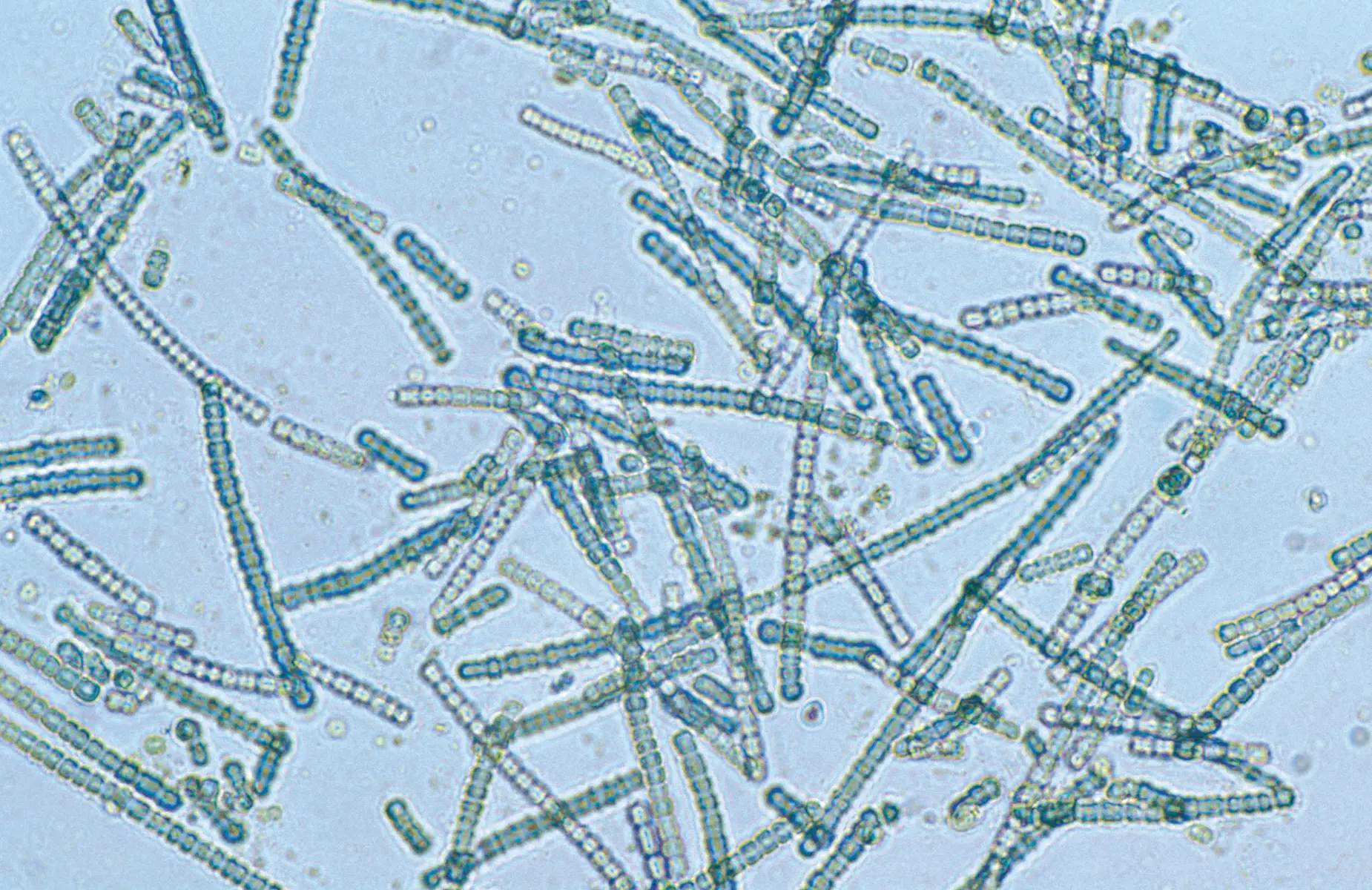

The single-celled organism Prochlorococcus marinus is probably the most abundant organism on Earth—and yet, for the most part, the cyanobacterium is known by name only to insiders. This may be due to its small size: The blue-green algae, which thrives in the uppermost layers of the oceans, has a diameter of only about 0.5 to one micrometer, which is about one-hundredth the diameter of a human hair.

Nevertheless, Prochlorococcus plays a prominent role in ocean life , accounting for approximately five percent of global photosynthesis. Marine phytoplankton thrives in more than three-quarters of the ocean's surface zones, produces about half of the ocean's oxygen (and is thus responsible for a quarter of global production), and forms an indispensable basis for the entire biological cycle of the world's oceans.

The results were surprising and not very encouraging: The cell division rate fluctuates depending on geographical latitude – influenced by nutrient levels, light, or temperature. After removing nutrients and sunlight from the equation, temperature emerged as a crucial factor for the well-being of Prochlorococcus: The cyanobacteria multiply best at 19 to 30 degrees Celsius. Above this limit, however, cell division plummeted dramatically – to only a third of the level reached at 19 degrees Celsius. The total cell count also followed this pattern.